About bumblebees without a future

Pesticide impacts and problematic authorisation processes

The EU authorisation for the controversial herbicide glyphosate expires in mid-December 2023. It is currently unclear whether the authorisation will be extended for another five years. Assessments by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which are relevant in this context, do not see this as a problem.1

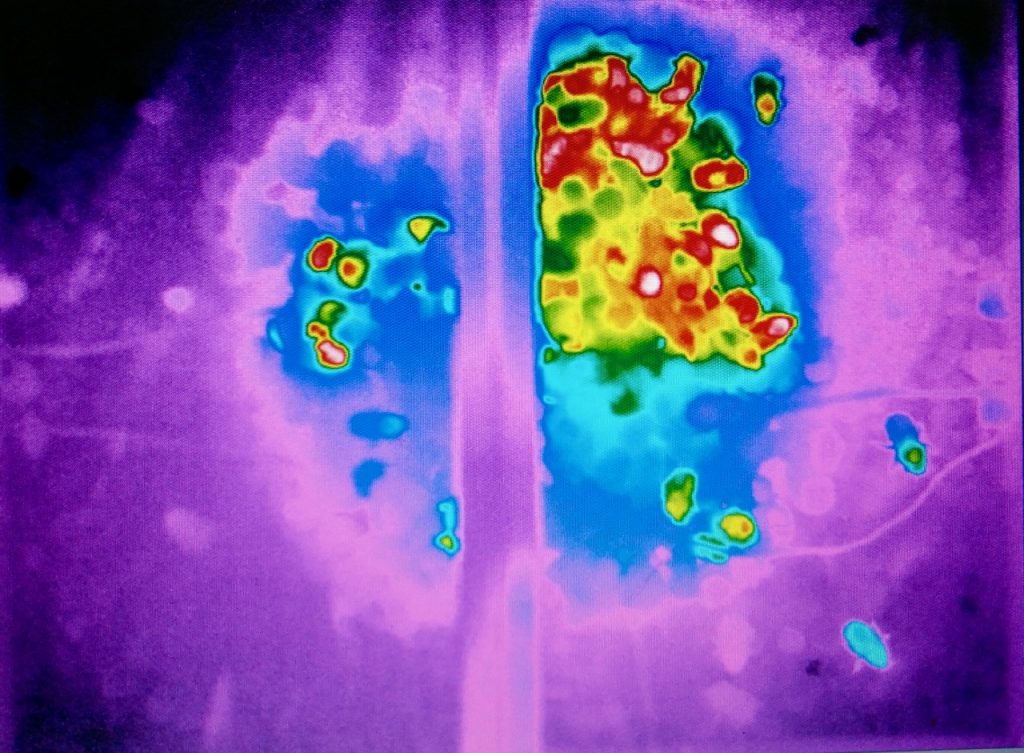

For example, biologist Dr. Anja Weidenmüller from the University of Constance has shown that bumblebees that ingest glyphosate through food (nectar or pollen) experience significant changes in their behaviour: “Like birds, bumblebees incubate their young in their nests. Temperature regulation is therefore essential for their survival. I have been able to show that glyphosate, a herbicide that has been used extensively around the world for 40 years, disrupts this regulation.2 This is despite the fact that it is classified as harmless to pollinators. But bumblebees can no longer keep their brood at the right temperature. This may sound like a minor effect. As a result, the colonies develop much more slowly, are much smaller at the end of the summer than unpolluted colonies, and are often unable to produce a new queen. This means that the colony has no future,” she stresses.

The scientist sees the approval process for pesticides as a major challenge: “We often know very little about the effects of pesticide use on the environment. This is partly because the approval processes that new products or active ingredients have to go through are toxicity tests,” explains Dr Anja Weidenmüller.

The Heinrich Böll Foundation also criticises this method of verifying the marketing of pesticides: “The indirect consequences for food chains and biodiversity, as well as the difficult-to-calculate effects of pesticide mixtures, receive little attention.”3

The scientist sees the approval process for pesticides as a major challenge: “We often know very little about the effects of pesticide use on the environment. This is partly because the approval processes that new products or active ingredients have to go through are toxicity tests,” explains Dr Anja Weidenmüller.

Image: University of Konstanz, Bild: Anja Weidenmüller2

What are toxicity tests?

Depending on the study design, a substance to be tested is usually fed to healthy insects such as honeybees with sugar water. After 24 or 48 hours, a count is made of how many individuals in a test group have died. If this number is not significantly different from a second group that received only sugar water, the product is considered non-toxic and is approved.

“However, many of these products have quite significant effects, for example on behaviour, and these effects are not captured in the current risk assessment and evaluation procedures,” criticises Dr. Weidenmüller.

It is calling for the authorisation procedures to be extended to include sub-lethal effects, i.e. effects that are not directly lethal. And in the light of current figures, this request seems more urgent than ever.

Although the World Nature Summit in Montreal decided to halve the use of pesticides by the end of 2022,4 at the same time, according to IVA data, pesticide sales in Germany did not decrease in 2022, but increased by 18.8 percent.5

The Heinrich Böll Foundation’s assessment in early 2022 that there has been little movement in the use of pesticides in Germany is also consistent with this. Only price fluctuations and weather conditions have influenced the amount used over the last 25 years. In Germany, this would remain stable at between 27,000 and 35,000 tonnes of pesticides per year.6 “And the decline in biodiversity is so dramatic that it’s happening quietly,” Dr. Weidenmüller stresses.

Back in 2017, a study by Dutch, German and British scientists showed that the number of flying insects has indeed fallen dramatically in large parts of Germany. According to the researchers, the mass of insects has fallen by an average of 76 percent since 1989.7 This has consequences for food chains and pollination processes.

Better procedures, more retreat space

Dr. Weidenmüller believes that one way to protect biodiversity is to improve the approval process for agrochemical products: “Parasite-free, well-fed test animals are simply not representative of the wild bee population. Better approaches are needed here, just as the toxicity test does not allow any conclusions to be drawn about sub-lethal factors. Behavioural aspects such as reproductive capacity also urgently need to be studied”.

In addition, unpolluted protected areas and refuges can offer recreational potential. In 2021, the German government committed itself to protecting 30 percent of the world’s land and marine areas by 2030. The EU Commission has already called these long-term goals into question for 2022, citing the loss of wheat exports due to the war in Ukraine. For example, it allowed the use of pesticides8 on ecological priority areas and fallow land, which are supposed to promote biodiversity.

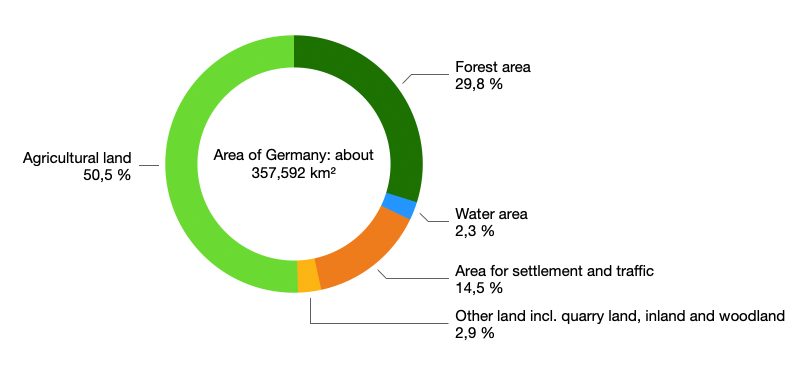

Protecting biodiversity is an arduous but rewarding task. Many small actions, such as wildflower meadows in parks and gardens, are helping. However, a reorientation at EU level would be much more effective, as almost 40 percent of the EU’s territory is used for agriculture. In Germany, the figure is over 50 percent.9

Land use (status 31.12.2021)

Figure based on: Federal Statistical Office 2022, FS 3 Agriculture and forestry, fisheries, R. 5.1 Land area by type of actual use 20219

Sources:

- https://www.efsa.europa.eu/de/news/glyphosate-no-critical-areas-concern-data-gaps-identified

- https://www.biologie.uni-konstanz.de/fachbereich/aktuelles/details/wie-glyphosat-die-brutpflege-bei-hummeln-beeintraechtigt20/

- https://www.wildbienen. https://www.boell.de/de/2022/01/12/zulassungsverfahren-fuer-pflanzenschutzmittel-gruenes-licht-fuer-risikende/wbarten.htm

- https://www.tagesschau.de/wissen/klima/abkommen-weltnaturgipfel-einigung-105.htm

- https://www.agrarheute.com/management/agribusiness/agrarchemie-viertel-weniger-pflanzenschutz-schon-moeglich-606363

- https://www.boell.de/de/2022/01/12/pestizideinsatz-deutschland-wenig-vielfalt-wenig-fortschritt

- https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0185809

- https://www.bmel.de/DE/themen/landwirtschaft/eu-agrarpolitik-und-foerderung/ukraine-oekologische-vorrangflaechen

- https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/daten/flaeche-boden-land-oekosysteme/flaeche/struktur-der-flaechennutzung#die-wichtigsten-flachennutzungen